Well, Central Banks are tightening monetary policy too fast. The ECB is ending Quantitative Easing just as the Eurozone economy is slowing rapidly. Abenomics in Japan is loosing some pace because the BOJ has boosted its balance sheet to more than 90% of GDP while still not hitting its 2% inflation target. Why stop now though? Full steam ahead, please.

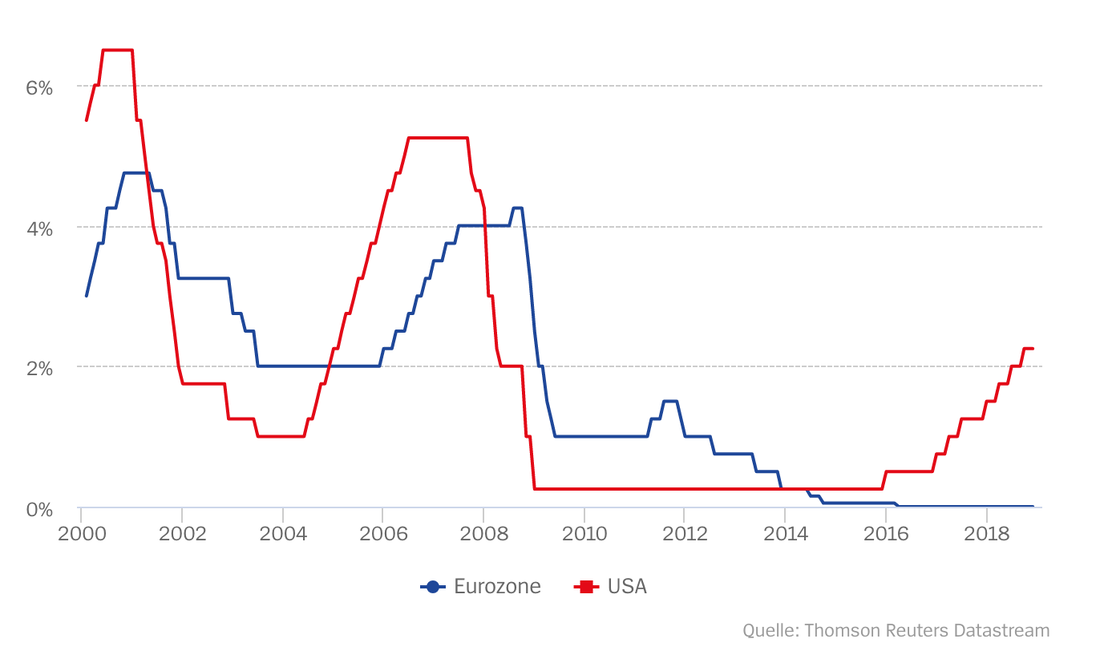

Finally, the Fed is increasing interest rates, probably too rapidly. The following graph shows how US rates and Eurozone rates have been diverging over the last few years.

The picture also shows that Eurozone interest rates follow US rates quite closely, usually with a lag of one to two years. That is because the Fed is the monetary superpower and providing liquidity for the entire world. My own research has shown that a significant variation of interest rate movement can be explained by global factors. See here.

The divergence between US rates and Eurozone rates cannot last forever. Since the ECB is committed to keep rates low for at least another half a year, the Fed will not be able to push up rates very much further, at least if it doesn't want to strangle the US economy.

Another US recession, most likely the result of too rapid tightening, would of course bring US rates down again, and in alignment with rates across most other advanced economies.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed