The significance of agglomeration effects and why geography matters

1. On the global scale

In the early 2000s Thomas Friedman famously proclaimed the death of distance in his book "The earth is flat", being the result of the new economy that emerged at the time. His hypothesis was that distance would not matter that much anymore in an economy where many products and services are increasingly produced and consumed online. Moreover, modern communication technologies would allow firms to relocate parts of their activities abroad as outsourcing becomes a viable option for an increasing share of the production process.

While it is certainly true that modern supply chains are increasingly global, a fact that the Trump administration was unable or unwilling to understand, this is the inevitable outcome of countries specializing with respect to their comparative advantage, and firms taking advantage of economies of scale in many production processes. The internationalization of global supply chains is ultimately to the benefit of everybody, since it allows for products to be assembled much cheaper than if the entire production process was located in just one country.

While the recent period of hyperglobalization has certainly meant that firms were much more flexible in their decision on where and how to locate globally, such decisions are based on a large number of economic factors that still give advanced economies the upper hand since low wages are just one single variable that might factor into a firm's decision making process. Arguably, of much more importance for many firms are in no particular order:

- Access to a highly educated workforce and technological advantages

- Access to high quality infrastructure

- Access to consumer markets

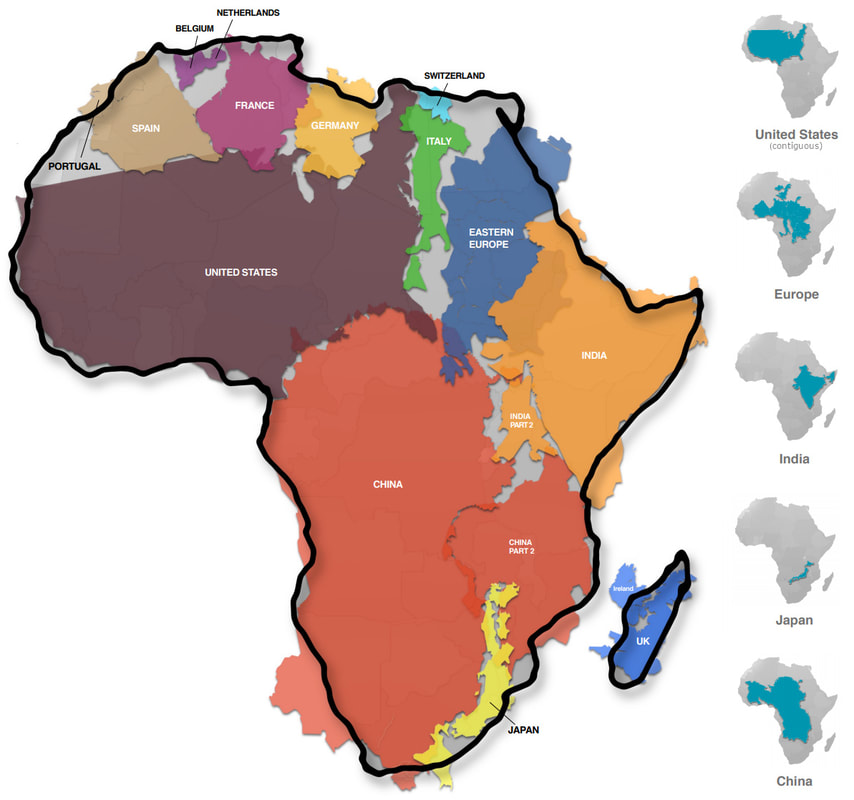

One of the problems of Africa as a continent, for example, is its enormous geographic size combined with its remoteness with respect to the world's most important consumer markets, which are North America, Europe, and South-East Asia. The distances and climate-related challenge, which will only increase with climate change, are probably too high to overcome in some cases to implement a export-dependent development strategy like South-East Asia did a couple of decades ago. Severe geographic disadvantages combined with the fact that most countries are still enormously underdeveloped does not bode well for many African economies in terms of a potential route towards industrialization.

Given that South-East Asia, especially China, has become the world's assembly line over the last few decades, there is very little African countries can do to challenge the status-quo (by the way, the same logic applies to Latin America). In the end, there is only so many fridges, TVs, and smartphones the world needs. And of course technology-intensive manufacturing, like Tesla cars or automatic vehicles, are produced in advanced economies, even though China might soon become a challenger in some of these areas as well.

While Friedman was thus right that production processes can theoretically be located anywhere in our globalized economy, the reality is that industrial centers are actually clustered even on a global level. Moreover, despite the rise of the new economy centered around the internet and service economy, economic activity has actually become much more concentrated on the national level, which is in direct contradiction with Friedman's claims.

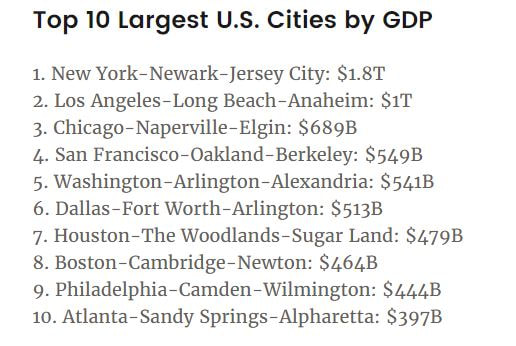

In fact, recent statistics show that economic concentration has increased sharply in most advanced economies, and especially in the US, where just a few large metropolitan areas have accounted for a large fraction of the total national GDP growth over the last couple of decades. The following statistics by McKinsey suggest that the top 30 cities in the US account for about 40% of the total population and produce about 50% of the national GDP, thus also pointing towards a clear correlation between city size (and population density) and productivity.

Enrico Moretti explains in his fantastic book "The new geography of jobs" that the economic geography has changed quite significantly in recent decades. Many small and medium-sized towns, but also some large cities like Detroit, have lost out over the last 30 years plus as the US economy has increasingly become deindustrialized. Classic industries like textile manufacturing, ship building, the automobile industry, etc. have become much less important in terms of the number of jobs they provide or even disappeared almost completely, thus initiating the relative decline of the Rust Belt. Detroit is obviously the ultimate symbol of the industrial decline with the city's population falling by more than 50% from about a 1.5 million in the 1970s to some 700.000 as of today. Such a spatial catastrophe in terms of population loss when it comes to a large city is practically unprecedented and no similar examples, at least of that scale, can be found anywhere in Western Europe.

Moretti's book exemplifies that over the last few decades it is a few major technology hubs, mostly San Francisco and the Bay Area, Seattle, and New York, which have contributed the most to American GDP growth. Some of those large cities have benefitted immensely from as agglomeration forces have increased in recent years, much in contrast to Friedman's hypothesis. It is only the cities that have a highly educated workforce provided by competitive international Universities that have been able to pull ahead whereas many old-fashioned industrial towns have stagnated, even more so in the US than in Europe.

Despite some of the highest wages as well as house prices in the world, it still makes sense for technology firms to cluster in the major tech hubs like Silicon Valley. Not only because that's where the skilled workforce is located, but also because of all the externalities that result from being close to other companies in the same sector with all the necessary infrastructure already in place, thus creating powerful effects of path dependence.

Of course, the recent surge in house prices in some of those metropoles has been so exaggerated that now even high-income earners are getting priced out of markets like San Francisco. The ultimate problem though is that regulations like zoning laws and other NIMBY policies prevent a more elastic housing supply response in the face of rapidly increasing demand, thus explaining the rising house prices.

Other work by Moretti actually suggests that a rapid expansion of housing supply in the major metropolitan areas in the US, especially on the West coast, could lead to a long-term increase of potential GDP of about 5 to 10%. There are few if any other macroeconomic policies that could lead to such a significant raise in living standards across the board.

What about Baltimore?

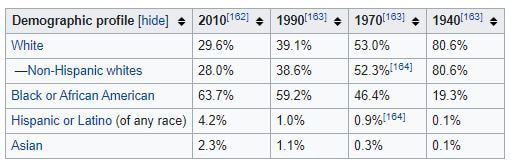

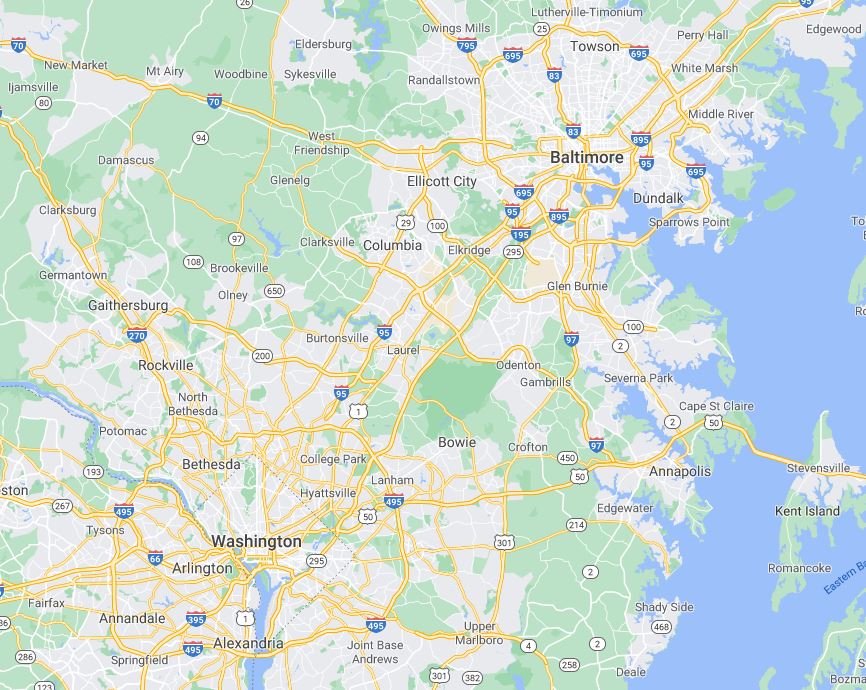

Baltimore is with about 600.000 inhabitants the largest city in the state of Maryland, which has a population exceeding 6 million inhabitants (national rank number 19). The state is located on the North-East coast of the US, and adjacent to Washington DC. A substantial fraction of the state's population is located in very close to proximity to the DC area as well as in the urban agglomeration of Baltimore. The proximity to the US capital also means that the state is relatively rich as it actually reports one of the highest median household income in the country with some 80.000$ plus. However, there is a substantial amount of inequality within the state, sadly enough very often along racial lines. The table below shows that the state's ethnic composition has changed quite substantially in recent decades. The city is now majority African-American populated and the poverty rate with more than 20% is extremely high and unemployment is higher than the national average.

While the port of Baltimore is still one of the largest in the US, it does not seem to be an important engine for job creation, given the high degree of automation in modern port facilities nowadays. Most of the current employment opportunities in Baltimore seem to be in the low-wage service sector, which also can explain the relatively low median household income in the Baltimore metropolitan area.

What is also interesting is that the proximity to the DC area does not seem to help the city that much, maybe because the competition effect outweighs the agglomeration effect in this case. What I mean by that is that the proximity to the DC area might in this case actually be a disadvantage, geographically speaking, because most of the job creation happens in the DC metropolitan area. At the same time, Baltimore is relatively poor and ethnically distinct so that most high-income people might not want to live there. Ethnic segregation has happened at the city level for decades and there is very little policy makers can do about these forces.

One can only hope that with the industrial decline that happened decades ago, the city can find other sources of job creation. More recently, a larger share of the jobs created have been in science and technology, clustered around Johns Hopkins University and the Hospital, which is precisely the kind of engine modern cities need to get over the industrial decline.

While the Corona shock has hit some major metropolitan areas like New York very hard in the beginning, I think that its importance is overstated and that reports about the death of some metropolitan areas are greatly exaggerated. Even if most major companies switch to some 50% remote work, you still have to go to the office the other 50% of the time.

The benefits from agglomeration will not disappear any time soon, and any ranking of major superstar cities in the US some 10 years from now will look very similar to a ranking in 2019. Path dependence matters, and if anything, has become more important than ever. Rural areas and old industrial towns have been loosing out for decades now while superstar cities have been gaining in importance.

This dynamic will not change any time soon even with Corona, especially now that a large share of the US population is gonna be vaccinated by the end of the summer. Even though some cities like New York have suffered enormously with the Corona shock, expect this to be only a very temporary affair. The forces of economic geography are simply too large, and not even remote work will change this. Expect the ranking below to look pretty similar in 10 years from now.

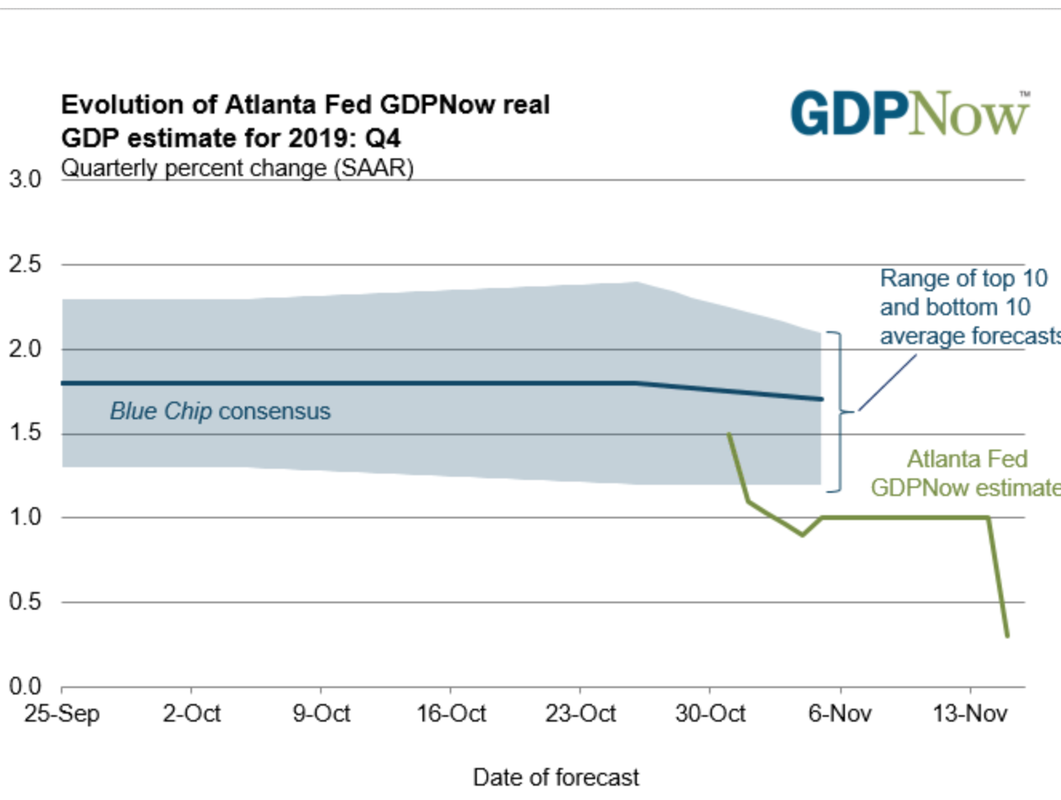

The new ambitious fiscal programs set up by the Biden administration in response to the Corona crisis might help cities like Baltimore that have been in relative decline for decades. It is especially the infrastructure program that could create new jobs and the ambitious support to families and low-income households that could make a difference. At the same time, a note of caution is warranted. Germany has transferred several trillions of Euros from Western Germany to Eastern Germany after the reunification. While this help did certainly do something to boost incomes in the East, it could not stop the relative decline of Eastern Germany in general. The regions has lost massively in population and has also experienced a brain drain for decades: the population of Eastern Germany has declined by more than 2 million, or almost 15% since the early 1990s. With the exception of some major cities like Berlin and Leipzig, all the fiscal transfers could not stop the relative decline of Eastern Germany in general, simply because the forces of economic geography have not favored that region. Similarly, there are regions and cities in the Rust Belt in the US that have suffered for decades and experienced a similar decline, mostly a result of deindustrialization as many heavy industries have been relocating to South-East Asia. Even the ambitious stimulus and fiscal programs set up by the Biden administration will most likely not put a stop these forces. Therefore, from a macroeconomic point of view, it is always better to help people than regions.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed